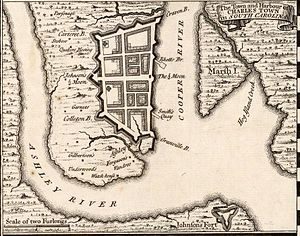

Charleston in 1733, map by Herman Moll

As one of the original thirteen colonies, South Carolina has long included an array of religious diversity belying its reputation for rigid conservatism. Historian Walter Edgar notes that South Carolina’s cultural heritage is very different from the other English colonies, being largely influenced in the 1630s by England’s richest colony at the time, Barbados.

Promotion of Barbados by the Lords Proprietor, distributed in England, Ireland and France, stressed both economic opportunity and freedom of conscience. During this time of the exodus of hundreds of thousands of Huguenots (French Protestants) from France, the pamphlet advertisements were intended to attract the wealthy, educated Huguenots to direct their flight for religious freedom to the new colony in the Caribbean. With the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, Huguenots began to swell the population of South Carolina, quickly becoming the most prominent ethnic group, after the English, and featuring prominently in colonial affairs. Eventually, the English began an intentional settlement of South Carolina, establishing the predominance of an Anglican religious culture.

St. James’ Church, Goose Creek, Berkeley County, South Carolina. 1938 photograph by Johnston, Frances Benjamin, 1864-1952. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

From the earliest years, African slaves entered South Carolina, arriving from the West Indies. They brought their indigenous religions, most notable Bakongo, from the Congo-Angola region, but there were also small numbers of Islamic Senegambians even then. Plantation journals record male slaves facing east for prayer five times a day, and the distribution of beef rations to some individuals during hog-killing times. The well-known Gullah culture of the lowcountry areas of the state can be traced directly to West African culture, and root workers are still prevalent in most parts of the state. Slaves began to convert (or be converted) to Christianity from early years, but brought much of their religious culture into their new religion, including variations of animism and the distinctive black musical approach to worship.

Prior to the American Revolution, non-Anglicans were referred to as Dissenters, but records show a harmonious collaboration among various denominations, the ministers of one group serving members of another which might be absent a minister for a time. The governor in 1770 wrote favorably about the diversity of Christian denominations in the colony, but noted that neither Roman Catholics nor indigenous African religions were welcome.

The 18th century cleric Charles Woodmason traveled extensively in the Carolinas during his career, concerned about the evangelical fervor characteristic of religious meetings in the frontier regions (e.g., New Lights, and “New Sects”). By this time Charleston was one of the largest centers of Judaism in colonial America, and is currently home to one of the four oldest synagogues in the country. Religious groups also included a Presbyterian meeting, an Independent-Congregationalist meeting with ties to New England, a Baptist congregation with ties to Pennsylvania groups, a Quaker meeting, an Arian congregation offshoot of the Baptists, a German-speaking Lutheran congregation, and a French-Calvinist Geneva-style congregation. Icons of the Great Awakening like John Wesley and George Whitefield visited Charleston. The overall Anglican culture, however, continued to be a force for moderation, and religious controversy was generally avoided.

The 18th century cleric Charles Woodmason traveled extensively in the Carolinas during his career, concerned about the evangelical fervor characteristic of religious meetings in the frontier regions (e.g., New Lights, and “New Sects”). By this time Charleston was one of the largest centers of Judaism in colonial America, and is currently home to one of the four oldest synagogues in the country. Religious groups also included a Presbyterian meeting, an Independent-Congregationalist meeting with ties to New England, a Baptist congregation with ties to Pennsylvania groups, a Quaker meeting, an Arian congregation offshoot of the Baptists, a German-speaking Lutheran congregation, and a French-Calvinist Geneva-style congregation. Icons of the Great Awakening like John Wesley and George Whitefield visited Charleston. The overall Anglican culture, however, continued to be a force for moderation, and religious controversy was generally avoided.

One exception to the avoidance of controversy was on the issue of slavery. The backcountry Methodists, Presbyterians, Baptists and Quakers were notably anti-slavery, the Methodist General Conference even decreeing in 1784 that slave-owning could justify expulsion from the church. In 1800 the Conference directed all Methodist clergy to sell any remaining slaves they owned. Unfortunately, by 1805 this policy was already dropped, more Baptist ministers than lay members owned slaves, many of the Quakers had migrated to the Midwest, and Presbyterian clergy who held antislavery positions had moved to Ohio. Other clergy tied abolitionism to women’s rights and other movements perceived to disrupt the social order established by the church.

Capers Chapel United Methodist Church, Chester, S.C.

By the mid-19th century Columbia was home to Baptist, Episcopalian, Lutheran , Methodist, Presbyterian and Roman Catholic churches, as well as a Hebrew Benevolent Society. Separate meetinghouses for black members of downtown congregations eventually developed into their own churches. At the beginning of the Civil War there were more black Methodists than whites, and about equal numbers of whites and blacks comprised the Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina. Predominantly black congregations spread rapidly across the backcountry. Following the war, most blacks preferred to separate themselves socially as much as possible from white society, and during this time many all-black denominations were created, the largest being African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AMEZ).

Religious denominations demonstrated a strong commitment to education, founding many of South Carolina’s colleges, e.g., Erskine, Furman, Newberry, Benedict and Wofford Colleges, and Allen University, during the 19th century. By the 20th century, and in the wake of culture-changing events like the Scopes trial, the perceived libertine culture of the 1920s, the subsequent Great Depression, and struggles for racial equality, religious leadership was often characterized by stringent cries against immorality, secular education, and alcohol.

Intrafaith groups like the Christian Action Council and the South Carolina Council on Human Relations were formed in the 1950s and 1960s to work for racial justice and continue to be active. In 1997 a religion subcommittee of a Commission on Race Relations appointed by the governor recommended the removal of the Confederate battle flag from the State House dome. Today conservative religious groups strongly influence the outcome of most elections, and legislative action on issues such as regulation of video poker machines, reproductive choice, blue laws, and same-sex marriage.

Intrafaith groups like the Christian Action Council and the South Carolina Council on Human Relations were formed in the 1950s and 1960s to work for racial justice and continue to be active. In 1997 a religion subcommittee of a Commission on Race Relations appointed by the governor recommended the removal of the Confederate battle flag from the State House dome. Today conservative religious groups strongly influence the outcome of most elections, and legislative action on issues such as regulation of video poker machines, reproductive choice, blue laws, and same-sex marriage.

Although South Carolina was a significantly-diverse colony and state until the mid-19th century, from then until about the mid-1950s it was markedly homogeneous, probably due to its immigration from other countries being the lowest in the U.S. Since that time, immigrants have included Greeks, Vietnamese and other southeast Asians, Pacific Islanders, East Europeans, East Indians, Middle Eastern, and Central and South American people, all bringing with them their cultures and religious practices. Numerous people self-identifying as New Age live in all parts of the state; many of these belong to Unitarian Universalist or Unity congregations.

Oyotunji Yoruba Villabe in Sheldon, S.C.

The first Sikh family moved to South Carolina in 1967, and the first Sikh gurdwara was built here in 1994 (members note that the climate here is very similar to hot and humid Punjab). The earliest records of Baha’i in the state date to 1910, with a biracial religious community forming in Columbia by 1938. The Baha’i have been prominent in interfaith work since the 1960s, being instrumental in the founding of the University of South Carolina-based Partners In Dialogue group. Jains in South Carolina typically visit Hindu temples in Greenville, Columbia and Augusta (Georgia) because they house a murti of the founder of Jainism, Mahavir. Numerous Buddhist groups exist throughout the state, and there are currently several large Hindu temples and a Vedic Center. At least eight masjids serve the Muslims of South Carolina, and Muslim leaders are active with interfaith groups such as Partners In Dialogue, Interfaith Partners of South Carolina and Women of Faith.

Buddhism in South Carolina, flowering primarily in recent decades, represents several major Buddhist traditions, including various paths of Theravada, Tibetan, Zen, Mahayana and Nichiren. Most practitioners are American-born converts, though there is also significant immigrant participation, which may be culture-specific. The Pluralism Project reports in 2004 the presence of six Buddhist centers centers in the Upstate, including one Laotian, two Cambodian (Theravadan), one Vietnamese (Chan/Pure Land), and a Theravadan center originally connected with Sri Lankan immigrants. At least five Columbia groups, the Ganden Mahayana Buddhist Center (New Kadampa), the Columbia Zen Buddhist Priory (Soto Zen) and the Shambhala Center and Dharmadhatu (Tibetan) are specifically focused on making Buddhism accessible to a Western audience. The Lowcountry is home to the Charleston Tibetan Society and a Zen group. Soka Gakkai International has a center in Columbia, with members in various parts of the state.

Buddhism in South Carolina, flowering primarily in recent decades, represents several major Buddhist traditions, including various paths of Theravada, Tibetan, Zen, Mahayana and Nichiren. Most practitioners are American-born converts, though there is also significant immigrant participation, which may be culture-specific. The Pluralism Project reports in 2004 the presence of six Buddhist centers centers in the Upstate, including one Laotian, two Cambodian (Theravadan), one Vietnamese (Chan/Pure Land), and a Theravadan center originally connected with Sri Lankan immigrants. At least five Columbia groups, the Ganden Mahayana Buddhist Center (New Kadampa), the Columbia Zen Buddhist Priory (Soto Zen) and the Shambhala Center and Dharmadhatu (Tibetan) are specifically focused on making Buddhism accessible to a Western audience. The Lowcountry is home to the Charleston Tibetan Society and a Zen group. Soka Gakkai International has a center in Columbia, with members in various parts of the state.

Native American leaders are still fighting for tribal recognition in South Carolina. There are a number of pipe-carriers and Sun Dance participants in the area, and some of these say they prefer the Lakota tradition, even though they are of Cherokee descent. Various African diaspora religious practices are common around the state, if not well-documented. An estimated 2,000 people in South Carolina self-identify as some form of Pagan.

The Coastal Interfaith Community, with strong leadership from the Unity Church of Charleston, has led interfaith efforts in the Lowcountry, and became the catalyst for renewed activity by the University of South Carolina. This has led to the formation of the statewide Interfaith Partners of South Carolina.

Sources

American Religious Identification Survey, 2008.

Edgar, Walter, South Carolina – A History, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, SC, 1998.

North Carolina History Project, John Locke Foundation, Raleigh, NC.

Stapleton, Ammon, Memorials of the Huguenots In America: With Special Reference to Their Emigration to Pennsylvania, Huguenot Publishing Company, Carlisle, PA, 1901.

Wells, Tracy, “Growing Religious Diversity in South Carolina: Implications for the Palmetto State,” 27 January 2004, project of the Pluralism Project at Harvard